Wolfgang Riede, how big a problem is space debris in the earth’s orbit?

Riede: At present, there are some 13,000 metric tons of non-maneuverable scrap permanently orbiting Earth. That’s a volume of around one and a half times the size of the Eiffel Tower. The earth’s orbit is filling up with satellite infrastructure at an ever-increasing rate. We expect the total mass of scrap and satellites to double or even triple by 2030. That’s just five years from now!

What exactly is space debris?

Riede: Objects ranging from the size of a grain of sand to really large pieces of debris. There are around 50 large objects up there. This includes all the rocket stages jettisoned during 68 years of space travel. And then there’s Envisat, the European Space Agency’s huge earth observation satellite, which gave up the ghost in 2012 for unknown reasons. There are also numerous small satellites that are no longer operational. Added to this is a collection of around 40,000 small pieces of scrap measuring over ten centimeters, which we can track from Earth. Plus, there are millions and millions of smaller bits of debris. And for most of these, we don’t even know where they are.

The rocket stages and the broken satellites — that makes sense. But where do all the small pieces of scrap come from?

Riede: They’re caused by collisions, both controlled and uncontrolled. Many are the result of antisatellite weapon tests. In the days of the Cold War, both the Americans and the Soviets wanted to show the other side that they were capable of using a rocket to shoot down a satellite. That’s still going on today. In 2007, China shot down one of its own satellites. Russia did the same in 2021. Both of these explosions left huge clouds of debris in the earth’s orbit.

Well, I guess there’s plenty of room up there …

Riede: There’s plenty of room, but this stuff is flying around the earth at a speed of up to 28,000 kilometers per hour. Remember, that’s almost eight kilometers per second! And each piece of debris moves along its own orbit. In other words, the debris is not flying synchronously, like the matter in the rings of Saturn, but in a wild, confused carousel. At the same time, each piece of debris rotates and therefore continuously alters its orbit ever so slightly. It can therefore happen that the International Space Station or one of the many functioning satellites is on a collision course with a piece of scrap metal. Were they to collide, this would release an immense amount of energy that is almost impossible to recreate on Earth. Laser technicians will understand what’s involved here: A collision in orbit with a particle of just one millimeter in diameter – in other words, tiny – generates an energy of 70 joules per square millimeter. That’s a lot! A satellite involved in such a collision would either be pierced by the particle or would completely disintegrate. Millions and millions of euros go up in dust. And back down on Earth, the infrastructure we rely on stops working. That’s the problem!

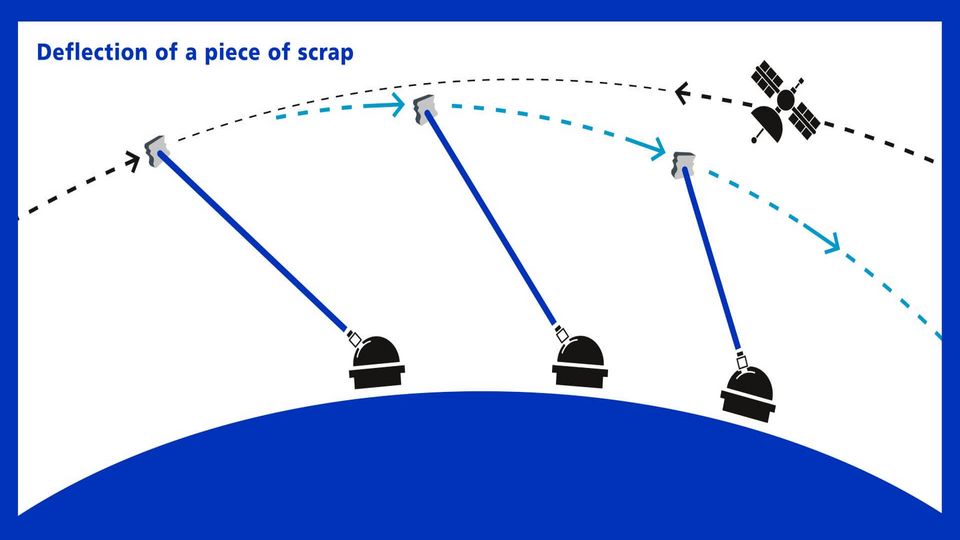

SCENARIO: A piece of scrap metal in orbit is on collision course with a satellite and threatens to damage or destroy it. Back on Earth, ten ground stations successively target the piece of scrap with a laser and thereby divert its trajectory so that the satellite is spared.

Whew! And what can you do about it?

Riede: There are two options. First, if we spot a collision in advance, the satellite must then take evasive action. The ISS does this all the time. But it gets refueled, whereas satellites don’t. Satellites are limited in the evasive action they can take. And when they do, this always impacts the overall service life, so it ends up costing a lot of money. Secondly, there are regular missions to clean up space. Vessels with robotic arms grab medium-sized pieces of scrap and hurl them down, as it were, into the earth’s atmosphere, where they burn up. But that’s expensive and out of the question for most pieces of scrap. In other words, both these options are only a make shift remedy. What we need is a proper solution!

And you believe you’ve found the right one?

Riede: I think so. Laser momentum transfer – or what we at the German Aerospace Center affectionately call “laser nudging.” Our team at the DLR has come up with a concept for how this can function. The principle is really easy to understand: The photons in laser light exert pressure. This is known as “light pressure” and is minimal. But when applied to a fast-moving piece of scrap in orbit, it can make all the difference. If we hit this piece of scrap frontally with a high-power laser, we can slow it down. And if we hit it from behind, we accelerate it. This means: If it slows down, it falls; if it speeds up, it rises. In other words, we can nudge it away from a collision path, from down here on Earth.

But there must be a problem, right?

Riede: We don’t need one laser station, we need ten – spread right across the globe.

Why’s that?

Riede: The light pressure exerted by the laser is minimal. We can only alter the speed of the pieces of scrap by ten micrometers per second. This means we have to apply the laser for a long time to achieve a significant effect. Imagine the target object appears on the horizon. At an overflight speed of eight kilometers per second, it remains visible for around ten minutes until it disappears below the far horizon. But we can’t fire the laser as soon as it appears on the horizon. That’s because the angle is still too flat and because the beam would have to travel through a lot of airspace. We’re only allowed to use airspace closed to civilian traffic, and that means only within a certain radius around the ground station. So, we have to wait, until it gets closer. Then we have to hit the object either frontally or from behind, since we want to either slow it down or speed it up. This halves the period available once again, so that we end up with a contact time of just two to three minutes. And that’s too short to deflect it enough. The method only works if there are ten ground stations each successively targeting the object over the course of ten overflights – a laser battery, as it were.

I see. But how can you even hit such a small thing in orbit?

Riede: That’s not a problem. The space industry has been using ultraprecise lasers over such distances for a very long time – for example, to detect pieces of scrap in the earth’s orbit. The tricky part lies elsewhere.

What’s the problem then?

Riede: The problem is how far in advance you can accurately predict a collision. That’s not an easy task. Like the weather, it becomes more difficult the further ahead you want to look. Our stations would need a few days’ advance warning. But we’re already working on this problem.

Has laser nudging been proven in practice?

Riede: We’ve never tried it in real life, but that’s normal for a space project. In addition to the ground stations, we will also need two satellites in constellation. These work in tandem to measure the impact of the laser beam and then report back to us. We don’t have these satellites yet.

Then everything we’ve been talking about so far is purely theoretical …

Riede: Not at all! In fact, I’m surprised at how fast our DLR project is now moving. ESA has commissioned us to design a ground station. We’ve been able to secure TRUMPF Scientific Lasers as a partner for the beam source. If all goes smoothly – financing, construction, choice of ground stations –we will deliver the proof of concept in five years. Okay, there are likely to be problems on the way. But we’re still talking here about a reasonable time frame to realization.

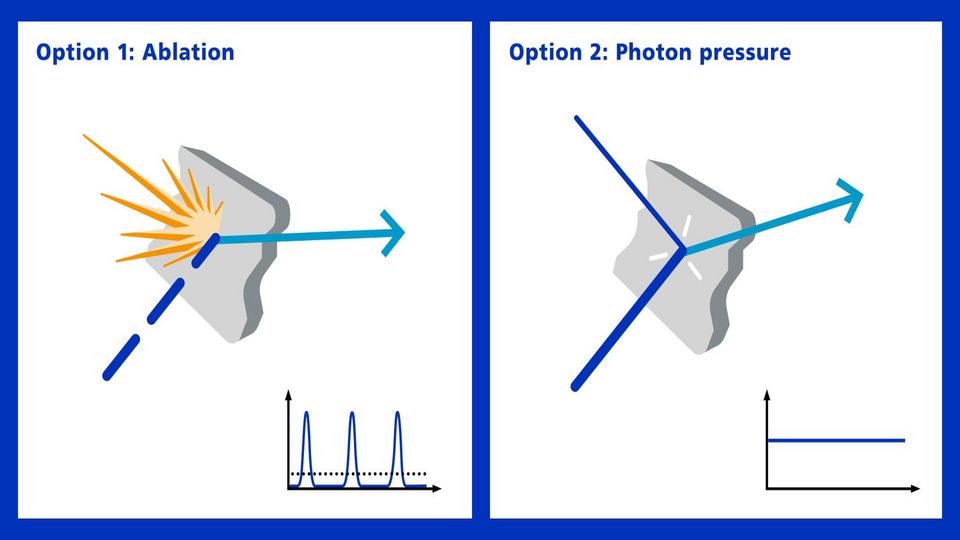

Left: A pulsed laser beam hits the object so hard that a plasma plume is created, thereby deflecting the object. Advantage: One overflight is enough, so less advance warning is required. Disadvantage: There is a risk that the object will disintegrate, producing more hazardous pieces of scrap.

Right: A continuous laser beam applies photon pressure to gently nudge the object into a different orbit. Advantage: There is no danger of the object disintegrating. Disadvantage: Up to ten overflights are needed before sufficient deflection has been achieved. More advance warning is therefore required.

How do you explain the sudden surge of interest in your project?

Riede: As I said, there’s going to be a massive expansion of satellite infrastructure in orbit – the Starlink network, for example, to provide mobile web services. Space debris is a big issue here. And it’s likely to get worse by several orders of magnitude because of this expansion, which in turn will generate more scrap. So, we’re going to need some kind of solution sooner rather than later.

Who will pay for laser nudging?

Riede: ESA member states are kick starting it through their contributions. But, ultimately, the plan is to market LMT as a service for private compa nies, organizations or states that want to protect their orbital infrastructure. Once stakeholders understand the scale of risk here, I think that funding the technology will be the least of any problems. Besides, in Germany we now have for the first time a federal minister with space travel in their portfolio, so we’re also expecting political support on the national level.